Arturo Ishbak Gonzalez

Intellectual Property Attorney

Brinks, Gilson & Lione

Technology is transforming innovation at its core, technological devices are emerging in new ways and big companies are competing every day to get out of the lab with new products that shape our world. Perhaps, Apple and Samsung are the most influential leaders in mobile technology right now with iPhone and Galaxy fighting every year to seduce consumers with new features. Then, the battle of big tech companies is not limited to the mobile marketplace; it is hitting the Courts around the world and the United Sates is not the exception.

One of the most important and recent decisions for the protection of product designs was issued by the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “Court”) in Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 786 F.3d 983 (Fed. Cir. 2015) on May 18, 2015. Product designs can be protected either by patent designs or trade dresses, in this article I will focus on the trade dress issue of the case.

Apple sued Samsung in April 2011. On August 24, 2012, the first jury reached a verdict that numerous Samsung smartphones infringed and diluted Apple’s patent and trade dresses in various combinations and awarded over $1 billion in damages. The diluted trade dresses are registered[i] and unregistered[ii] defined in terms of certain elements in the configuration of the iPhone.

The district court upheld the jury’s infringement, dilution, and validity findings over Samsung’s post-trial motion. The district court also upheld $639,403,248 in damages, but ordered a partial retrial on the remainder of the damages because they had been awarded for a period when Samsung lacked notice of some of the asserted patents. The jury in the partial retrial on damages awarded Apple $290,456,793, which the district court upheld over Samsung’s second post-trial motion. On March 6, 2014, the district court entered a final judgment in favor of Apple, and Samsung filed a notice of appeal. On May 18, 2015, the Court reversed the jury’s findings that the asserted trade dresses were protectable.

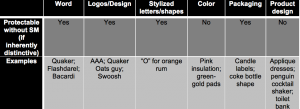

Now, what is trade dress? Trade dress has been defined by the Courts as the totally of elements in which a product or service is presented. Trade dress can be either a product design or a package design. This distinction is important because product packaging can be protected without proof of secondary meaning, but product designs need to show acquired distinctiveness aka secondary meaning.

Secondary meaning recognizes that words or designs with an ordinary and primary meaning of their own may by long use with a particular product, come to be known by the public as specifically designating that product. To understand these concepts the following chart might be useful:

[i] The ‘983 trade dress claims the design details in each of the sixteen icons on the iPhone’s home screen framed by the iPhone’s rounded-rectangular shape with silver edges and a black background.

[ii] A rectangular product with four evenly rounded corners; a flat, clear surface covering the front of the product; a display screen under the clear surface; substantial black borders above and below the display screen and narrower black borders on either side of the screen; and when the device is on, a row of small dots on the display screen, a matrix of colorful square icons with evenly rounded corners within the display screen, and an unchanging bottom dock of colorful square icons with evenly rounded corners set off from the display’s other icons.

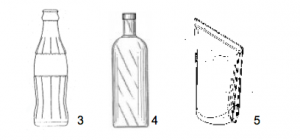

The following are examples of product packaging trade dresses:

On the other hand, the following are examples of product designs trade dresses:

Trade dress only protects non-functional designs and product features. A design or feature is functional if it is essential to the use or purpose of the article or if affects the cost or quality of the article. While only some utilitarian advantage is considered functional, a design is functional if the product works better in the particular shape claimed. In this regard, the trade dress owner bears the burden of proving non-functionality.

As a result, it is more difficult to claim product configuration trade dress than other forms of trade dress. In our case, the 9th Circuit required a high bar for non-functionality of product configuration considering that “Apple conceded during oral argument that it had not cited a single Ninth Circuit case that found a product configuration trade dress to be non-functional.”

The Disc Golf factors test for functionality are: (i) whether the design yields a utilitarian advantage, (ii) whether alternative designs are available, (iii) whether advertising touts the utilitarian advantages of the design, and (iv) whether the particular design results from a comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture.

For the sake of good order today, I will first analyze the decision regarding the unregistered trade dress asserted by Apple.

For the first factor; the utilitarian advantage, Apple emphasized a single aspect of its design, beauty, to imply the lack of other advantages. But the evidence showed that the iPhone’s design pursued more than just beauty.

Moreover, Apple conceded during oral argument that its trade dress “improved the quality [of the iPhone] in some respects.” For instance, Samsung identified the following utilitarian advantages: the rounded corners improve “pocketability” and “durability” and rectangular shape maximizes the display that can be accommodated, the bezel protects the glass from impact when the phone is dropped, and the icons allow users to differentiate the applications available to the users and the bottom dock of unchanging icons allows for quick access to the most commonly used applications.

For the second factor, Apple asserted that there were “numerous alternative designs,” however; it failed to show that any of these alternatives offered exactly the same features as the asserted trade dress.

In connection with the third factor; the advertising of utilitarian advantages, the Court held that Apple failed to show that, on the substance, the Apple’s demonstrations of the user interface on iPhone’s touch screen involved the elements claimed in Apple’s unregistered trade dress and why they were not touting the utilitarian advantage of the unregistered trade dress.

The fourth factor considers whether a functional benefit in the asserted trade dress arises from “economies in manufacture or use,” such as being “relatively simple or inexpensive to manufacture.” In this case, the Court held that for the design elements that comprised Apple’s unregistered trade dress, Apple pointed to no evidence in the record to show they were not relatively simple or inexpensive to manufacture.

On the other hand, for the asserted registered trade dress, the undisputed evidence showed the functionality of the registered trade dress and shifted the burden of proving non-functionality back to Apple. Apple, however, failed to show that there was substantial evidence in the record to support a jury finding in favor of non-functionality for the registered trade dress on any of the Disc Golf factors.

Consequently, the Court reversed the district court’s denial of Samsung’s motion for judgment as a matter of law that the registered trade dress was functional and therefore not protectable.

Finally, in the next article I will analyze the decision regarding the design patents issue, which might be helpful to understand the similarities and differences between the scope of protection of trade dresses and designs patents, as well as the benefits of protecting either both or relying on the protection granted by only one of them.

Arturo Ishbak Gonzalez

NBC Tower, Suite 3600, 455 N. Cityfront Plaza Drive

Chicago, Illinois 60611-5599

Twitter: @ArturoIshbak

[1] The ‘983 trade dress claims the design details in each of the sixteen icons on the iPhone’s home screen framed by the iPhone’s rounded-rectangular shape with silver edges and a black background.

[1] A rectangular product with four evenly rounded corners; a flat, clear surface covering the front of the product; a display screen under the clear surface; substantial black borders above and below the display screen and narrower black borders on either side of the screen; and when the device is on, a row of small dots on the display screen, a matrix of colorful square icons with evenly rounded corners within the display screen, and an unchanging bottom dock of colorful square icons with evenly rounded corners set off from the display’s other icons.

[1] U.S. Reg. No. 1,057,884

[1] U.S. Reg. No. 3,254,923

[1] U.S. Reg. No. 1,418,517

[1] Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 786 F.3d 983 (Fed. Cir. 2015)

[1] 199 F.3d 1009 (9th Cir.)

[1] 529 U.S.