This is the second article in a two-part series analyzing the decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Samsung’s appeal to a jury’s verdict finding of design patent infringement, the validity of two utility patents, and the damages awarded for such design and utility patent infringements.

The decision was issued by the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “Court”) in Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 786 F.3d 983 (Fed. Cir. 2015) on May 18, 2015. This article will analyze the design patents issue of the case.

Apple sued Samsung in April 2011. On August 24, 2012, the first jury reached a verdict that numerous Samsung smartphones infringed and diluted Apple’s patent and trade dresses in various combinations and awarded over $1 billion in damages.

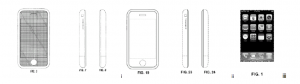

The infringed design patents were U.S. Design Patent Nos. D618,677 (“D’677 patent”), D593,087 (“D’087 patent”), and D604,305 (“D’305 patent”), which claimed certain design elements embodied in Apple’s iPhone:

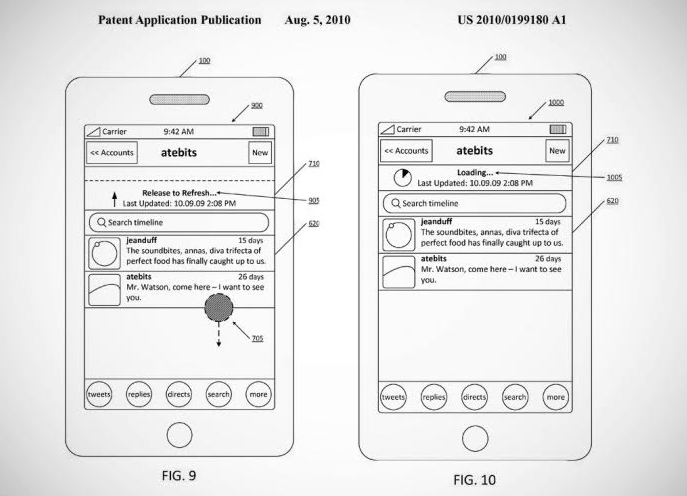

The infringed utility patents were U.S. Patent Nos. 7,469,381 (“‘381 patent”), 7,844,915 (“‘915 patent”), and 7,864,163 (“‘163 patent”), which claimed certain features in the iPhone’s user interface.

The district court upheld the jury’s infringement, dilution, and validity findings over Samsung’s post-trial motion. The district court also upheld $639,403,248 in damages, but ordered a partial retrial on the remainder of the damages because they had been awarded for a period when Samsung lacked notice of some of the asserted patents. The jury in the partial retrial on damages awarded Apple $290,456,793, which the district court upheld over Samsung’s second post-trial motion. On March 6, 2014, the district court entered a final judgment in favor of Apple, and Samsung filed a notice of appeal. On May 18, 2015, the Court affirmed the jury’s verdict on the design patent infringements, the validity of two utility patent claims, and the damages awarded for the design and utility patent infringements appealed by Samsung.

Now, what is a design patent? It is a design that consists of the visual ornamental characteristics embodied in, or applied to, an article of manufacture. Since a design is manifested in appearance, the subject matter of a design patent application may relate to the configuration or shape of an article, to the surface ornamentation applied to an article, or to the combination of configuration and surface ornamentation. A design for surface ornamentation is inseparable from the article to which it is applied and cannot exist alone. It must be a definite pattern of surface ornamentation, applied to an article of manufacture.

The following are examples of design patents:

In our case, Samsung raised three issues before the Court; functionality, actual deception, and comparison to prior art, all of them in the context of the jury instructions and the sufficiency of evidence to support the infringement verdict.

Regarding the functional aspects in the asserted design patents, the Court found that the jury instructions, as a whole, already limited the scope of the asserted design patents to the “ornamental” elements through the claim constructions: the design patents were each construed as claiming “the ornamental design” as shown in the patent figures.

In connection with the actual deception, it is important to recall that a design patent gives the owner the right to prevent others from making, using, or selling a product that so resembles the patented product that an “ordinary observer” might purchase the infringing article, thinking it was the patented product. The ordinary observer is generally deemed to be the retail purchaser of goods of that particular type rather than an expert, who would be less likely to be fooled.

Likewise, It is important to bear in mind that the comparison is not made on a side-by-side basis. The test involves a hypothetical ordinary observer who, being aware of the patented design, encounters for the first time the product alleged to infringe.

The ordinary observer pays as much attention as one would typically use in deciding to purchase such a product. A further refinement to the test is that the comparison must be made between the two articles as they would appear in use.

In the standard of the infringement test, the Court first must determine what ornamental features of the patented design are not shown in the prior art and whether one or more of these were appropriated by the product alleged to infringe. If not, there is no infringement. If there was appropriation of one or more of the unique features, then a second test is applied.

One looks at both the similarities and differences between the two products to determine if there is sufficient overall similarity to deceive the ordinary observer. If so, infringement exists.

Unlike the product trade dress analyzed in my last article, design patent infringement rights cannot be avoided by properly labeling the goods. Informing the ordinary observer as to the state of the art might better highlight the novel features of the claimed design, but asking whether a consumer is confused or deceived by the imitator at the point of purchase misses the point of design patent protection. Infringement should be measured against the issued design patent and concepts related to validity should not be coming led in the analysis.

With all this considerations, the Court found Samsung’s arguments unpersuasive because Apple’s witnesses provided sufficient testimonies to allow the jury to account for any functional aspects in the asserted design patents. Additionally, the witnesses testified on the similar overall visual impressions of the accused products to the asserted design patents such that an ordinary observer would likely be deceived. Apple’s experts also testified about the differences between the asserted patents and both the prior art and other competing designs. The jury could have reasonably relied on the evidence in the record to reach its infringement verdict. Consequently, the Court concluded that there was no prejudicial legal error in the infringement jury instructions on the three issues that Samsung raised.

Arturo Ishbak Gonzalez

NBC Tower, Suite 3600, 455 N. Cityfront Plaza Drive

Chicago, Illinois 60611-5599

Twitter: @ArturoIshbak

[i] D’677 patent

[ii] D’087 patent

[iii] D’305 patent

[iv] D307,508 (Reebok)

[v] D517,789 (Crocs)